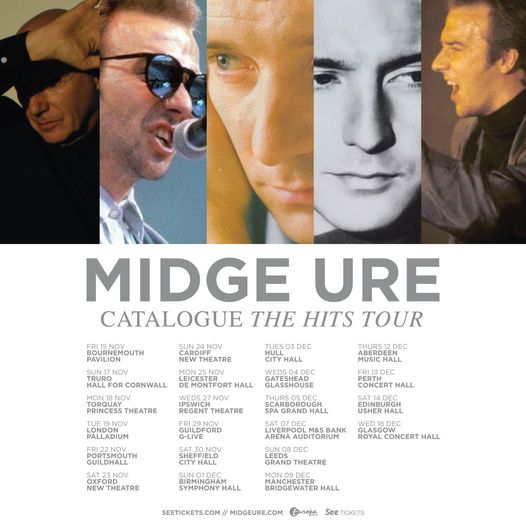

Having celebrated his 70th birthday at the historic Royal Albert Hall, Midge Ure is keen to continue the celebration of his life in music with a major UK tour later in 2024 – as he tells Lucy Boulter – showcasing his 50-year song catalogue…

They say that nothing is ever lost when we carry it in our hearts. And for those of us still openly mourning the end of the remarkable ‘80s music scene, our hearts swell every time one of the decade’s icons returns to the stage.

And in just a few months’ time, one of the greatest titans of them all will be coming to a town near you. Midge Ure is going back on the road.

Midge’s bio needs little retelling. His first number one came as lead singer of Slik, whose 1976 chart hit, “Forever and Ever”, catapulted him into teenage heartthrob status.

He had turned down Malcolm McLaren’s offer of lead vocalist in the Sex Pistols, in favour of Slik, but things came full circle a little later when he joined founding Pistol, Glen Matlock, in his new band – Rich Kids.

Midge’s self-proclaimed role as an early adopter of new technology was becoming critical at this point. Electronic synth’ was emerging as a nascent trend in Europe, opening up a whole new spectrum of sound, and he was keen to see what he could do with a synthesiser. This led him to form Visage, fronted by the late Steve Strange.

A brief spell with Thin Lizzy followed – between 1979 and 1980 after he saved the US tour. Midge also claimed a co-write on Lizzy’s “Black Rose” album [the song “Get Out Of Here”] and he did a couple of tours with the band as co-lead guitarist with Scott Gorham, before leaving to pursue an opportunity as frontman in the revival of a band called Ultravox.

And by the mid-‘80s, Midge was flying high with a solo career. The rest, as they say, is history.

Jim v Mij!

It might be worth explaining how Midge got his name, since these things become lost in the mists of time. It’s hard to picture the music scene of the last 50 years with a James Ure instead of a Midge Ure!

One of his very early bands, Salvation, shaped his future more than he might have foreseen at the time. At his first rehearsal, he was told by the bass player, Jim McGinlay, that there was room for only one Jim in the band and instead the 18-year-old newcomer was to be called Mij – his name said backwards. Mij quickly became Midge, Salvation became Slik, and Midge never left the stage.

To us as teenagers in the ‘80s, it really seemed like the whole decade belonged to Midge. Take these few examples.

Ultravox simply dominated the music scene for years, and the fact that “Vienna” was held from the top-spot in 1981 by an infamous novelty record (Joe Dolce’s “Shaddap You Face”) almost certainly outraged most Ultravox fans.

Joining “Vienna” in the pantheon of anthems that still to this day summon us straight back to that decade was “Fade to Grey” – co-written and produced by Midge.

The New Romantics were a cultural explosion, courtesy of the club nights at Billy’s in Soho and later the Blitz in Covent Garden. Midge was at the heart of that, one of the luminaries of the day alongside the club DJ – his Rich Kids and Visage bandmate Rusty Egan.

Band Aid / Live Aid Hero

Every single week, we huddled in front of the family TV to worship at the altar of “Top of the Pops”, the theme tune for which, for most of the ‘80s, was “Yellow Pearl” by Phil Lynott – co-written by Midge.

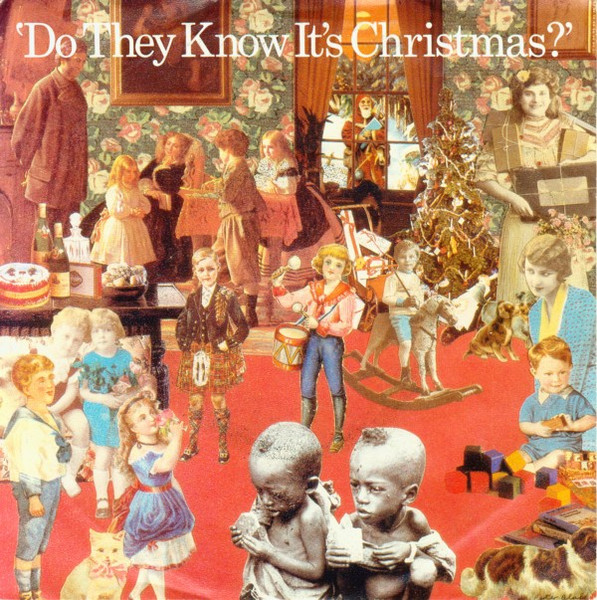

The charity supergroup Band Aid in 1984 saw SARM Studios in Notting Hill packed out with the big hair and the even bigger vocals of everyone who was anyone back then, to record the perennial seasonal hit “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” – which was co-written and produced (and even partially pre-recorded with some of its melody tracks) by Midge.

And then there’s Live Aid. Even nearly 40 years later, it seems inconceivable to chat to Midge and not talk about it.

To me as a woman now of a certain age, there aren’t enough superlatives to describe Live Aid. An instant sell-out with more 160,000 people in London’s Wembley and Philadelphia’s John F Kennedy stadia, plus simultaneous concerts around the world, and a global audience of nearly two billion people thanks to one of the biggest satellite link-ups of all time.

Midge helped curate performances from a host of all-time greats and contemporary chart-toppers, among them David Bowie, Queen, Status Quo, The Who, Dire Straits, U2, Elton John, Paul McCartney, Paul Young, Nik Kershaw, Billy Ocean, Joan Baez, Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Madonna, Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin, Mick Jagger, Tina Turner, and more.

As a snapshot in time, that day in July 1985 showcased talent and compassion, pulled together in a technical feat of broadcasting. More importantly, it raised some £50million on the day.

I’m excited to talk about Live Aid with a man at the very heart of it, having interviewed some of its performers on these very pages. Event production has always struck me as a swan swimming upstream – seemingly effortless above the surface, but kicking its webbed feet like crazy beneath the water. Was Live Aid like that, with such an ambitious array of artistry (and perhaps artistic ego)?

Turns out Midge had a different set of concerns – the anxieties of a performer fronting one of the most successful bands of the decade.

“I was panicking about what the band [Ultravox] was going to sound like, because there was no sound check. At that point, we [Ultravox] were doing five-hour sound checks because of the technology we used, so I was thinking about all the technical things; what if we walk on in front of all these people and nothing works!

“Bob [Geldof], on the other hand, had a band [Boomtown Rats] who could just plug into the amplifiers and play, and all he has to do is walk on and sing! And he was the one running round like a headless chicken and doing all the backstage interviews and stuff – and there were lots of those. But I have to say, the ‘give us your effing money’ moment is a myth! He never actually said it.”

History books…

Many of history’s big milestones present themselves quite quietly, revealing their enormity only through the lens of hindsight. And in that context, I wonder if Midge sensed the cultural impact of Live Aid, in the moment.

“Not really. I mean, we knew it was big, but we’d been building up to it for three months by then. For us, it didn’t just happen overnight as it seemed to the public. We’d been talking about this thing, the possibility, how it could work. And this was a time when we had to do all the arrangements by sending telexes and making telephone bookings!

“But you’re right. I didn’t realise how significant it was – not just as a music event but also as a social event. In fact, I think I only realised a couple of years later. We’d just moved out of London, to near Bath, and the little girl next door came round to hang out with my daughter – and she said to me: ‘oh, we’ve read about you in our history lesson today.’ And I thought: wow, hold on a second! What do you mean? And she told me how they had read about Band Aid and Live Aid; it was in their history books.

“That’s when it hit home. You think: wow, I didn’t see that coming. Wood for the trees, that’s basically what it is. When you’re in the middle of it all, and you’re embroiled in the nuts and bolts of it all, you don’t see much impact.”

Now, this might be the gloom of my middle age talking, but I don’t think we’ll see the like of Live Aid again. I ask Midge about this, hoping he’ll be more optimistic – but he shares my cynicism, though with much better informed reasoning.

“I think the music world has changed beyond recognition. Remember that in ’84/’85 when Band Aid and Live Aid happened, music was the be all and end all. We didn’t fill our time with social media and phones and streaming television shows. That didn’t exist. Music was our thing. Back then, in your spare time you were either playing sport or you were listening to music. Of course, it’s depleted a huge amount now. So music isn’t the same powerful platform it was, and you might never see something like that again. Wow. You’re making me nostalgic now…”

Fantasist

So, knowing what he knows now about this rise and fall of the music industry, would he make the same decision to be a musician if he had his time again? Midge doesn’t even pause to consider my question.

“I didn’t have a choice! When I was a kid, my mother used to say that if you shook me, my head would rattle because it was full of broken bottles – meaning that my head was full of nonsense.

“I was a fantasist. I would dream of doing this. I could sing, you know; I had a voice long before I was allowed anywhere near a guitar. Mind you, I could draw a guitar before I could pick one up! It was my fantasy, but the reality was that it was so far out of reach, it was never going to happen. Playing in a band, yes, you can do that; little gigs in your neighbourhood – which is exactly what I did for many, many years. I was learning my trade, I suppose.

“But the idea of being signed, and making a record, and doing world tours – all that stuff was still in my head. But it was broken bottles, absolute fantasy. Like kids growing up dreaming of being a world-class footballer one day…you can play football in your back garden, but that doesn’t mean you’re going to get that opportunity. You need tenacity, a little bit of talent, and a lot of luck.”

Looking back at Midge’s rather glittering bio, from teen heartthrob in Slik to, dare I say, national treasure status, I think there’s a fourth ingredient in his recipe for success. I think his trajectory owes no small amount to his personal reputation among people with whom he nurtured long-lasting relationships.

For example, Phil Lynott didn’t ask a stranger to save the day halfway through Thin Lizzy’s Black Rose US tour in 1979, to sub the sudden departure of guitarist Gary Moore. He asked his friend Midge Ure, whose character and talent he knew and trusted.

For example, [now Sir] Bob Geldof didn’t ask just anybody to collaborate with him on the spectacle that was Band Aid and Live Aid, as he responded in high emotion to Michael Buerk’s watershed report from Ethiopia. He asked Midge, whom he had known since Rich Kids opened for the Boomtown Rats in Camden in 1977.

This speaks not only to Midge’s loyalty to his professional friendships, but also to his reputation and his value as a colleague. People buy people every bit as much as they buy talent and expertise.

Unintentionally proving my point about personal character being as important as talent, Midge is quick to downplay this with a humility I imagine was deeply ingrained in him as a small boy growing up in a two-roomed tenement in a town in Glasgow’s outskirts.

“It’s that thing about luck again. I just think I’ve been stupidly lucky; in the right place at the right time. Had someone else been standing next to Paula Yates when Bob called, having just watched BBC News, it would have been someone else co-writing and producing that song, someone else as his sidekick!

“But yes, when someone comes to you and asks you to direct a video or produce a song for them, there is a trust there. They’re asking you specifically because they like what you do and they trust you will give them what they’re after.

“Talent you can work on, but timing is luck.”

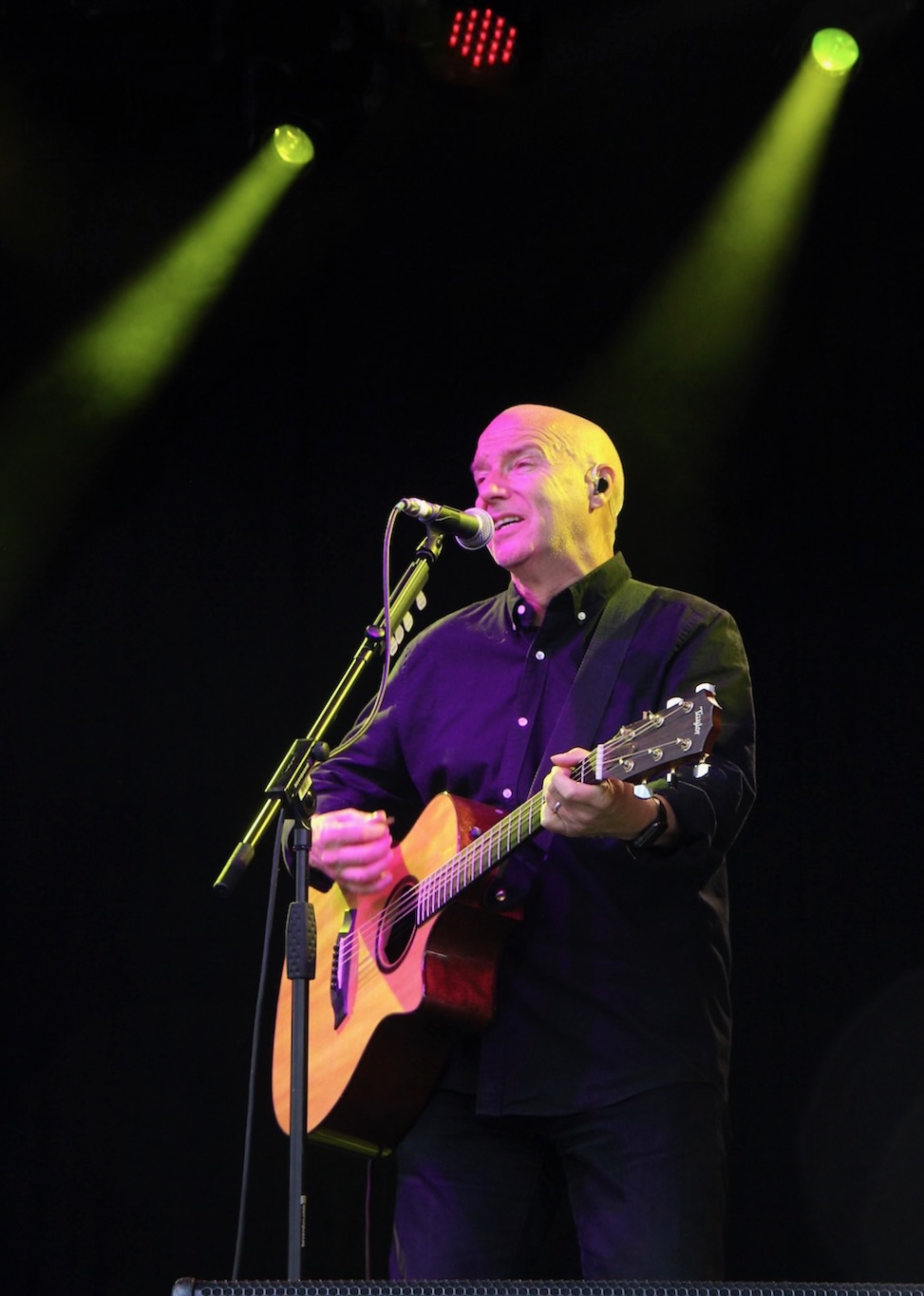

Midge describes his upcoming tour as a retrospective – though he says it’s more than just a ‘greatest hits’ event.

“I’ve called it ‘Catalogue’ because it encapsulates everything in my back catalogue, from the moment I started writing and recording. But not just the songs people expect to hear, because they’re the songs we play all the time! I’m trying to cherry-pick the songs people don’t hear very often, but are particular fan favourites.

“I haven’t got the setlist organised yet, but I’m contemplating starting from the late ‘70s, with Rich Kids and Visage, then Ultravox and solo, and taking it all the way through. Obviously I can’t do it all – I’d be on stage for weeks on end!”

The tour is a fair heft through November and December – he’ll be trekking the length of Britain, from his home in Bath to his hometown of Glasgow. But let’s be honest, being out on the road in the middle of winter is surely a young man’s game, and Midge has just turned 70. Would he not rather be taking things a bit easier?

“You know, during lockdown I looked in my diary – and there was nothing in it. And I haven’t seen that since I was 15. And to have nothing lined up for getting out to perform was quite frightening.

“It’s a drug, isn’t it? It’s not the desire for adulation. I really don’t think it’s that at all, although it’s lovely when that happens. It’s like scratching an itch, you know; you have to go out and do it.

“Touring is something I’ve done all my life. I was touring long before I was allowed in a recording studio to make any music, and to me it’s like blinking or breathing; I don’t even think about it. It’s something I still thoroughly enjoy. I enjoy the camaraderie. I don’t go playing golf, or skiing trips with the boys. I’m quite an insular character, and satisfying that nomad in me is enjoyable for me. But it’s a busman’s holiday, isn’t it!

“Touring is a double-edged sword though, because when you start the tour, things are never one hundred per cent, ever. Doesn’t mean it’s bad, but just that it’s not how you envisaged it. And by the time you finish the tour, you’re thinking: oh God, I wish I was back in the studio! The moment you’re back in the studio, you want to be back out touring again. The grass is always greener!

Much as he loves touring, it’s evident that his family life is just as important to Midge, and I imagine he and his wife, actress and yogi Sheridan Forbes, are feeling the emptiness of their nest near Bath. His four daughters are all grown up, with ages ranging from 37 to 25.

And his role as Dad has been never more important than in the last few months, since the death in November of his former wife Annabel Giles, mother of his eldest daughter, Molly. The 64-year-old actress and novelist, who was married to Midge in the late ‘80s, had been diagnosed with an aggressive glioblastoma just a few months earlier.

“It’s been horrible for Molly with her Mum dying, absolutely horrible. It makes it even more difficult when it comes out of the blue. When things happen in a very short space of time, it’s quite devastating. It was absolutely horrendous for her. But we’re a very supportive family. We all support each other.”

Arise Sir Midge!

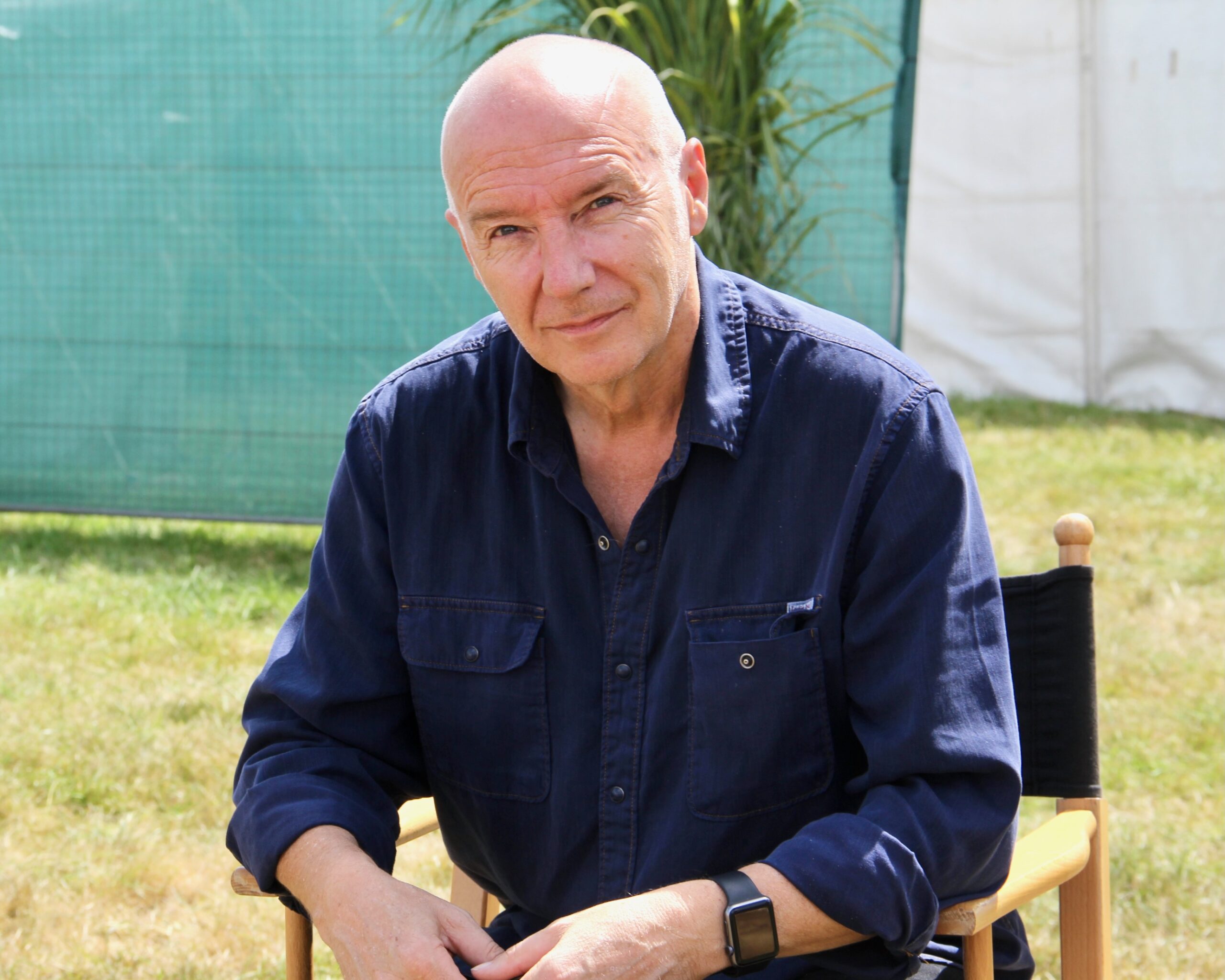

As our wide-ranging conversation comes to a close, with Midge facing a busy day in his recording studio at his second home in Portugal, I have a burning question for Midge; a mystery that I cannot explain.

He has an OBE, awarded in 2005. He has won an Ivor Novello, a Grammy, a British ASCAP, and has more gold and platinum discs than you could shake a stick at. He has a remarkable five honorary doctorates in appreciation of his contribution to culture, charity work, music, and humanitarian achievements.

He has helped to raise hundreds of millions of pounds for charity – not only through Band Aid (for which he remains a Trustee) and Live Aid, but also through his involvement with charities such as The Prince’s Trust (acting as Musical Director for several of its annual concerts), Breakthrough Breast Cancer, Live 8, and Save the Children UK, for which he was a long-time Ambassador.

So where on earth, I ask him, is his knighthood?

“In the post!” he quips. “You know, I didn’t ask for any of those things. They are thrust upon you when you least expect them, and neither Bob nor I did any of this for any kind of self-gratification, or for gongs. You know, it’s lovely, the OBE, and it’s just nice to have it – but it doesn’t get you anywhere!

“I remember talking to [legendary screenwriter and co-founder of Comic Relief] Richard Curtis, when I got it. He congratulated me, and he had a CBE so I asked him what to do with it! He said: ‘Nothing! It doesn’t even get you a decent table in a restaurant!’ But I think it’s a lovely thing.”

So would he accept a knighthood – if, say, I mounted a campaign for it? “You campaign, and I’ll find out!” he laughs.

Words: Lucy Boulter

Photos x 3 [marked *]: Alex Asprey

Recent Comments