“Bowie’s thing was just to kick the music business up the arse”, reveals the man who helped him do just that.

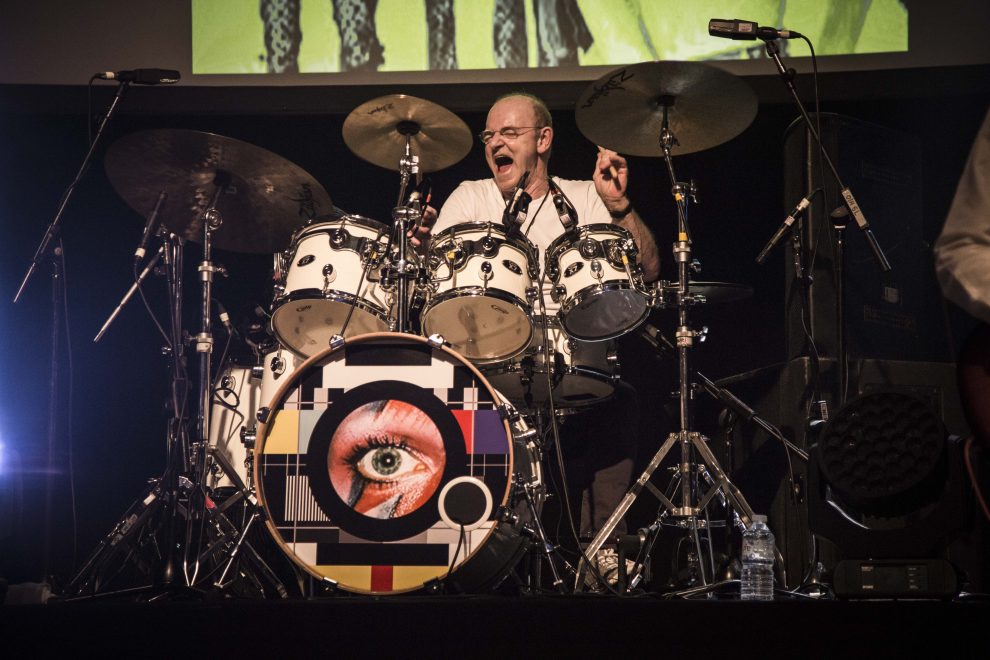

Woody Woodmansey, celebrated drummer in The Spiders From Mars, tells Music Republic Magazine’s Lucy Boulter about his amazing Mach 5 rocket ride to stardom with the late music icon…

Shortly after David Bowie’s death in 2016, his long-time collaborator and Holy Holy band member, Tony Visconti, called the “Blackstar” album “his parting gift to us”. But as Bowie-mania shows no sign of abating two-and-a-half years later, we have to wonder if the great man is keeping that gift going; orchestrating more and more entertainment for us from whichever lucky planet he now orbits.

Woody Woodmansey doesn’t think so. And he should know, being one of a handful of people in the world who were part of the Bowie nucleus – and, arguably, part of the most iconic and important era of Bowie’s long and glittering career. “I think he’d just sit back in obscurity and chuckle,” says Woody, when I ask him what he thinks Bowie would make of the festivals, the tributes, the statues, the tours.

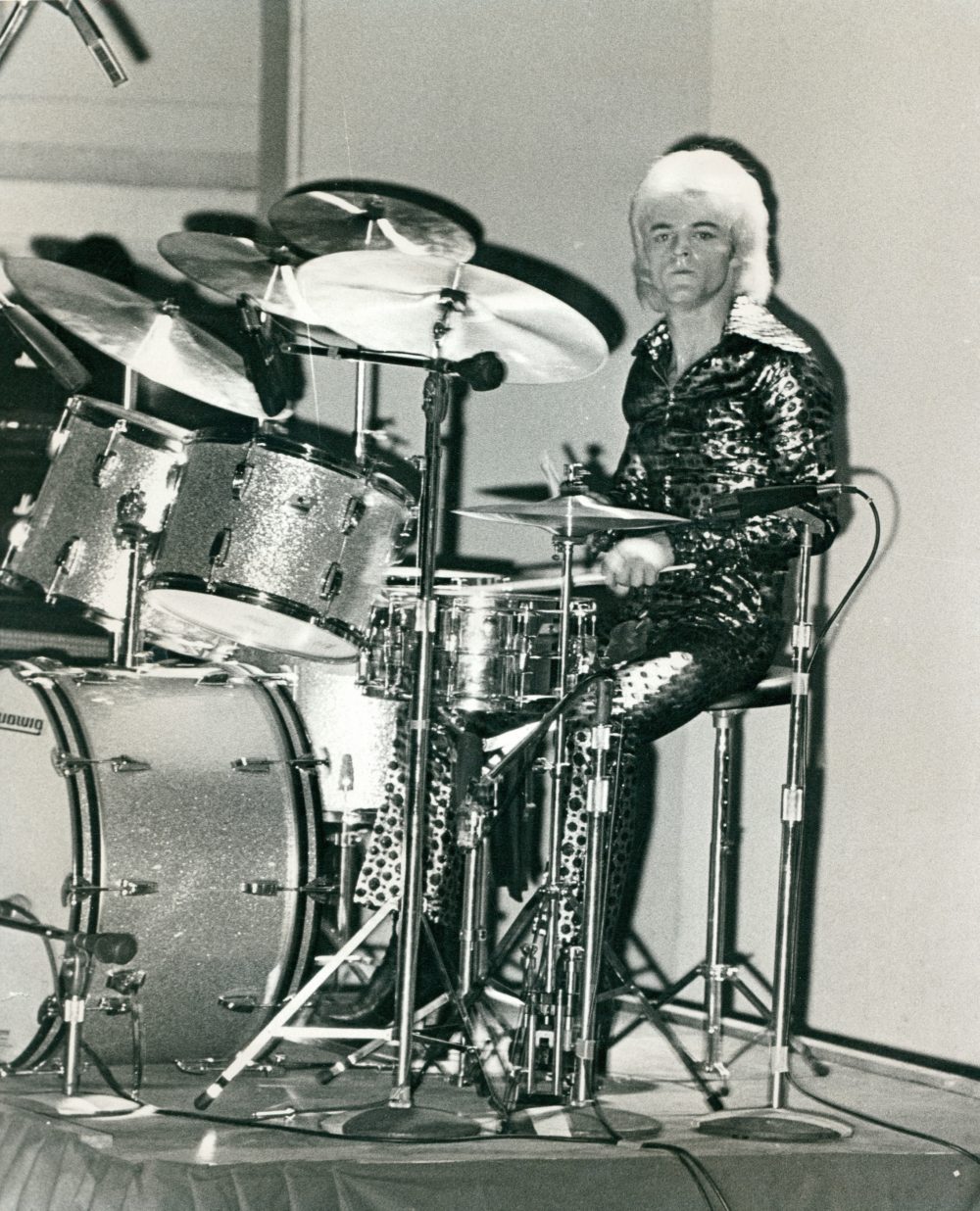

“I don’t think he particularly wanted all that. I think part of him would like the fact the music lives on, but Bowie’s thing was just to kick the music business up the arse.” Woody is the last surviving Spider from Mars, the drummer in Ziggy Stardust’s eponymous band along with guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder.

He created the beats for four studio albums – “The Man Who Sold The World” (1970), “Hunky Dory” (1971), “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars” (1972) and “Aladdin Sane” (1973). He also features on two live albums – “Live at Santa Monica ’72” (recorded in 1972, but released in 2008) and “Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture” (recorded live in 1973, but released in 1983).

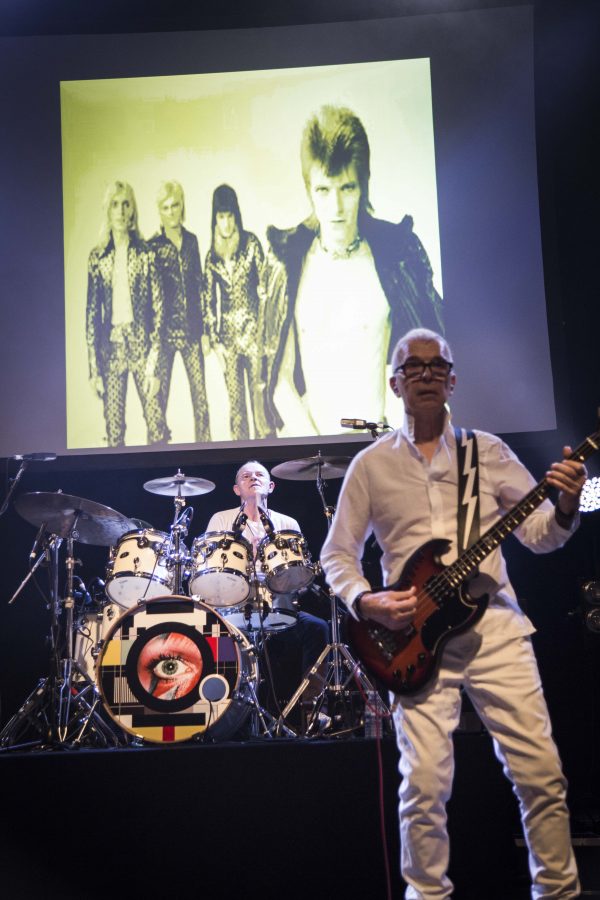

Now he’s getting back on the road with his old buddy and collaborator, Tony Visconti, in what some might say is the ultimate tribute to Bowie – tracks played by the musicians who helped create them.

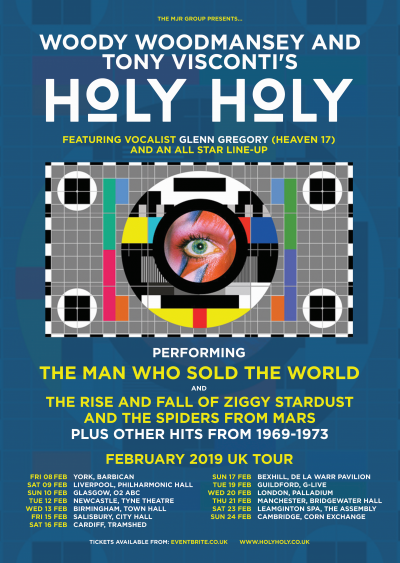

Holy Holy

But Holy Holy is neither a tribute band nor a reaction to Bowie’s death. The band formed with Bowie’s knowledge and blessing, for reasons he well understood. The initial premise of the band was to tour “The Man Who Sold The World”, a track from which the band draws its name. Woody and Tony are both instrumentalists on the album, and this was Tony’s first producer credit with Bowie.

“For various reasons, ‘The Man Who Sold The World’ never got played live, not even by David…he and the band were all living on beans on toast at the time that album came out and there was no means to do it. And I thought: that would be great to do,” Woody tells me.

“I didn’t even know if we could do it, because it was quite a challenging album, but if we did, I knew I had to get Tony on bass. I wasn’t too sure if he’d be interested, but I’d just about finished telling him my idea and he said – yeah, wherever you’re playing, I’ll be there.

“I thought I’d have to spend two hours talking him into it, but he said that David and he had spoken many times over the years about their regret that they never went out and played that album. For Tony, this was on his bucket list.

“Tony had just done an album with Glenn Gregory, from Heaven 17, and knew he could kill it vocally, so we set up a rehearsal in London. At the end of the first song everyone just fell about laughing – but it was a good laugh. It sounded so powerful, so good. It was like we’d just finished the album, you know?”

The seed for the idea, however, grew rather more organically. “The whole thing started by accident, in a way,” says Woody. “I got a call…I think it was 2012…from the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, and I thought – ooh, that’s posh! And they said they’d like to interview me, in front of 300 people, for an event about Bowie.

That was Bowiefest, staged to coincide with Bowie’s 65th birthday and the 40th release of “Ziggy Stardust”. “I’d never done anything like that, so I was a bit reluctant. But I figured that I might like it or I might not, but at least I’d know. And I went and I did it, and it was a really, really good night. I was surprised to find I enjoy talking as much as I enjoy drumming!

“The Institute had also put together a band to do a set of Bowie tracks at the Latitude Festival that year. It was mostly early music, the stuff I’d worked on. They asked if I’d like to guest on two tracks from my time with Bowie – and I chose “Five Years” and “Ziggy Stardust”.

They had some good names in the band – people who credit their musical interest to Bowie and his influence – including Clem Burke from Blondie on drums, and Steve Norman from Spandau Ballet. I thought that would be great fun to do.

“What I hadn’t reckoned on was that for most of the set, I’d be standing at the side of the stage watching Clem play all my parts! I just wanted to get up and throw him off the drums, basically. The set got such a good response that the band carried on, doing other gigs. Then Blondie got a tour and Clem wasn’t available, so they asked me if I’d do it. I said I would as long as I didn’t have to audition. So we did a few gigs like that, but it was ‘bit and piece’ and I started thinking about my idea for “The Man Who Sold The World”…”

The first iteration of Holy Holy toured the UK and later Japan in 2014, with a core assembly of Woody, Tony and Glenn, with James Stevenson and Paul Cuddeford on guitars, Berenice Scott on keyboards, and Jessica Lee Morgan (Tony’s daughter) on vocals, sax and guitar.

Other contributors to this supergroup have included Marc Almond, Gary Kemp, Steve Norman, Glen Matlock and Clem Burke – along with vocals from Mick Ronson’s sister Maggi, his daughter Lisa and his niece Hannah. It’s fair to say the band’s Bowie credentials are impeccable.

Given that Holy Holy was formed for such a tight objective, did Woody see a future for it beyond that first set piece? He admits he was surprised by the audience reaction to an album that is essentially dystopian (though some might say prescient), dealing with Nietzsche concepts, the future of man and the uprising of machines.

Freaky

“I didn’t have a plan to put a band together to do Bowie material. I just thought it would be nice to do that album. But then I realised that we were playing very dark songs and the audience was singing along like they were pop songs – which was a great response though quite freaky, you know!”

Surely ‘freaky’ would not come as a shock to a man who, at the age of just 19, left his small Yorkshire town and moved into Bowie’s home at Haddon Hall in Beckenham, sleeping on a mattress at the top of the stairs?

“I thought Bob Dylan was like Yogi Bear on drugs”

Sharing living quarters and a basement rehearsal room with Bowie, his wife Angie, Tony Visconti, Mick Ronson, and Roger Fry (Bowie’s driver and roadie), with occasional Sunday morning visits from Bowie’s mother, Peggy (who naturally worried that Bowie wasn’t eating enough).

“I remember the first day I met him. He played me albums of his folk stuff, and it really wasn’t my genre. I’d never been into folk music; I thought Bob Dylan was like Yogi Bear on drugs or something – that’s what it sounded like to me!

“It was probably because I thought there was generally no good drumming on it, so although I appreciated it was another medium of art, it was nothing to do with what I did. But it was what David did. But then David picked up his guitar and played me ‘The Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud’ [the B-side of “Space Oddity”]. There was just me and him in the room, and he was five feet away.

“And you know, I’d gone in there with a mental checklist – does he look good as a frontman, does he dress well, can he write, is he intelligent – because I’d just turned down a really good and steady job as assistant foreman at the Vertex spectacles factory in Driffield for this! But at the end of that song, I just thought – wow, well he can write!

“I always thought he was a cut above most others for that reason – and the fact that he had that ability to not fill in all the dots. He just pointed you in the direction of a song, and you took it. He gave you enough for you to create your own story. You can ask a thousand people what ‘Life on Mars’ is about, and you’ll get a thousand different answers.”

This worries me slightly, as a Bowie fan for 30 years or more, as I’ve always secretly thought that to understand the meaning of life, I just needed to crack the lyrics of “Quicksand”, an amazing track on “Hunky Dory”. Woody just laughs at my idea, and suggests I try the lyrics to sister-track “The Bewlay Brothers” instead. I’ll take that as a polite suggestion to give up now.

But while we’re talking about giving just enough to create your own story, I’m interested to know more about the freedom Bowie was legendary for affording his musicians. Some of his most iconic tracks are down to the treatment given to them by the band – think about Mike Garson’s thrashing piano on “Aladdin Sane” (I’ve stood next to him while he played that live, and I can tell you he even uses his elbows). Think about Trevor Bolder’s mellifluous bass line on “John I’m Only Dancing”.

It’s even true of backing vocals – think about Luther Vandross’ and Ava Cherry’s interpretation on “Young Americans” just a few years later. And you can’t help but think about the spine-tingling drum track that opens the seminal “Five Years”. I ask Woody how that came about.

“Well, we chatted about it, and we knew it was about the end of the world and pretty depressing. David said – I need a beat that sets it up for what’s coming. I thought – oh yeah, put it on my shoulders! I remember at the time being a little bit tempted by a nice drum roll and a cymbal splash and a flashy bit – but then I said to myself – it’s the end of the world, you’re not gonna do that!

Bowie’s Tears

“I played us in, and David just said – that’s it! We all just got into the mood of it being the end of the world. I remember when we recorded it, he was actually in tears. He was doing the vocal and he was actually crying.”

There’s a dichotomy here for me: the artist who had the good sense to hire talent and then actually use it, versus the artist who thought about every minuscule point. Anyone who visited the global “David Bowie Is…” retrospective will have seen the notes, the drawings and the attention to detail; so, was he a micro-manager?

“No, not really,” Woody tells me. “I mean, he drew things out for himself, and what he wanted to get across. But he only ever once told me what drum beat to play, on all those albums.” I am tempted to guess which one, but time is tight so I simply ask…

“It was ‘Panic in Detroit’. He’d played it to me while we were on the road (in Detroit, ironically), so I had it in my head. I’d worked out a riff – it was very John Bonham, as I’m a big Bonham fan. Then we went into the studio in, I think, San Francisco and I started playing the beat I had in my mind.

“David just stopped and said – no; just play a Bo Diddley beat, really simple. He started humming it, and I said – but you haven’t heard all the other drum fills I have for it. He said – I don’t wanna hear them.

“Immediately I knew he was right, the bastard”

“I tried again – there are like 10,000 drummers who could play it like that, and he said – no, not like you’d do it. So, I started playing the Bo Diddley beat and immediately I knew he was right, the bastard! It was so simple and effective.

“It was the only time he ever told me what to play. I mean, we didn’t have time to get instructions. He’d be writing something in the lounge in Haddon Hall, and I’d be making toast or something, and he’d shout – Woody! I’ve finished one, come and listen.

“I’d listen and tell him I liked it, and he’d decide that was one to record on Monday. But come Monday, we’d get into the studio and be ready to go on it, to be told – no, no, we’re not doing that one now, I’ve just finished this one.

“We’d hear it twice and then we’d go…the tape would be rolling, and I’d be thinking – where’s the chorus? Is there a chorus in the middle? Do we end on a chorus?! And we learnt pretty quickly – we weren’t going to get five or six goes at a song!

“We’d listen to the first take in the control room at Trident (Studios) and think about what to do in the next take, and he’d say – no, that’s it. We did ‘Life on Mars’ on the third take (and we’d got the first two takes right!). ‘Jean Genie’ – first take. ‘Starman’ – first take.”

Spellbound

“Starman” might be one of Bowie’s most famous songs, thanks in no small part to the iconic moment on BBC TV’s Top of the Pops, when Bowie stared and pointed down the camera as he sang – “I had to phone someone, so I picked on you”; it’s the moment in which thousands of Bowie fans say they were spellbound by this man. And yet it might never have come about, but for the record label’s refusal to release the influential “Ziggy Stardust” album…because they didn’t think it had a single on it.

“So, David went back home that weekend and knocked out ‘Starman’. He played it to us and we all said – well, that’s a single! He could do that when he felt like it…he always had the ability to write a hit song. But he didn’t always want to do that. His message for a particular album, or a particular style he was in, was more important to him than whether he made a hit record with it.”

And as for “Life on Mars” – well, Woody says even the band was taken aback by that one. “I remember when we’d finished it, Ken Scott [the producer on “Hunky Dory”] said – come and have a listen to the mix. We all went in, and I looked along at the other three – all of us had our jaws dropped.

“I think it was me who asked – is that us? I mean, it was good when we’d finished our bits, but it’s always a little bit raw when you’ve just recorded it, and Ken put the sparkle on it. We knew it was good, and we were really proud of it. We just didn’t know if anyone would GET it. It would have to be one of my favourites of the Bowie tracks I played on – along with ‘Five Years’ and ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide’.”

While we’re talking favourites, I ask Woody which of Bowie’s later catalogue he wishes he’d played on. I thought it might be hard to answer (I know lots of Bowie fans and very few can name a single favourite) and indeed it is. Woody’s choices are quite diverse: “I really like ‘Scary Monsters’; I’d like to have played on that. I like ‘Heroes’ as well, which I sometimes get to play live anyway. And a bleak one – ‘Cat People (Putting Out Fire)’; I really like that track.”

The latter track featured Bowie’s lyrics on part of a film score written by Giorgio Moroder, later re-recorded for the “Let’s Dance” album. More than twenty years later, film impresario Quentin Tarantino lifted it from its relative obscurity, onto his soundtrack for “Inglourious Basterds”.

A friend of mine is currently discovering Bowie’s music, a newcomer in his late 20s. Listening recently to “Hunky Dory” for the first time, he said it made sense of a lot of other bands…that in that one album he could hear the influences for Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, even Arctic Monkeys.

So, while Bowie and his band were working at breakneck speed, putting down iconic tracks in one or two takes and, frankly, making it up as they went along – did they have any inkling at all that they were setting the pace for generations of bands to come?

“No! To be honest, no. David’s thing was just to make the music industry more exciting, more colourful, more adventurous – and we were into that as well. But we didn’t think that 40 years later, ‘Life on Mars’ would still be played on the radio every week. “You couldn’t think like that. We just did our best job, for that track and on that day, and hoped that people would like it.”

It’s clear to me that Woody has enough anecdotes to fill this conversation ten times over and more, but for all the highlights of a career spanning decades, I can’t ignore the well-documented issues he had with Bowie and his then-manager, Tony Defries. There was the famous showdown when he and Trevor Bolder discovered they were paid less than other band members.

There was the infamous moment when Bowie announced Ziggy’s retirement live on stage at the Hammersmith Odeon – which was news to them although not to others. And the final insult – a phone call from Tony Defries on Woody and June’s wedding day in July 1973, to tell him he was out of the band. Yet, Woody has always called Bowie his friend. I ask him how he reconciled those tensions.

“I guess at first I wasn’t like that. You could think – but you’re my friend, how could you? But you have to take a look back and understand why, what was going on, who was around, what influence they had. Then you understand.

“…rocket ride from obscurity to major star…”

“And I got to see him a few years later, in France. We talked through all of that stuff…the bad things said on both sides. He told me he’d come to realise that his rocket ride from obscurity to major star was in the Spiders era.

“He said he knew he’d never get that again, that it was the enjoyable bit, and that he had us guys to thank for that. He’d never said that while we were with him, so that handled a lot of things for me. And, you know, I don’t think he gave much attention to the financial situation and how it was all done. He was very much a 24/7 artist.”

Both Woody and Tony remained big names in the music industry. Woody continued with the Spiders from Mars for a time without Bowie, enjoyed critical acclaim with his band U-Boat, and worked with artists such as Paul McCartney and Art Garfunkel.

Tony collaborated with Bowie on a great number of his albums throughout his career, right up to his last album, “Blackstar” in 2016, but was also in demand with artists such as Marc Bolan, Wings, Moody Blues, Manic Street Preachers and Morrissey.

Woody is clearly under no illusions about Bowie’s influence on his life, beyond the three-and-a-half years in which their careers exploded. “Even without him sitting down and teaching you, you could observe him and learn things. Playing live with David…well, of course the notes were important, but we could do that, we were good musicians; it was getting across the spirit of the song that was important, and we put that in with Holy Holy.

“We make sure the atmosphere is exactly right; that’s what people have come to see, and we’ve stayed true to that. I mean, I’m a better player now than I ever was and so is Tony. So much experience under your belt, you know,” says Woody, who at 67 is on top of his game.

Last call

Holy Holy was on tour when Bowie died, arriving in Toronto as the news broke, sending shock-waves around the world. Only two days earlier Tony had phoned Bowie in the middle of Holy Holy’s New York gig, and the crowd sang “Happy Birthday” to him. ‘Thank you. Ask them what they think of ‘Blackstar’? Good luck with the tour,’ said Bowie, before ringing off.

It’s hard to imagine how even the most experienced artists could carry on with that night’s performance; of course, they had honed their craft with the consummate professional, for whom the show would always have gone on.

It’s perhaps fitting: two of the tiny, tight-knit group from those early Haddon Hall days, still working together and bringing those early albums to life right at the end of Bowie’s story.

Little wonder (pun intended, to honour the Bowie 1997 top 20 hit from “Earthling”) that we miss Bowie so much. Thankfully we have those closest to him to keep his legacy alive.

- Holy Holy’s 13-date UK tour in February 2019, kicks off in York on Friday 8th Feb and closes in Cambridge on 24th Feb 2019. Tickets on sale now: www.eventbrite.co.uk / www.holyholy.co.uk

By Lucy Boulter

Photo credits:

Main Woody drums shot at top of page: Dan Woodmansey

Woody in Spiders From Mars days – bleached hair shot: Mick Rock via Holy Holy Tour PR

Bowie & Woody shot: Getty Images via Holy Holy Tour PR

All other pics: PR supplied