The second and now regular monthly column from celebrated US-based “A-List” session musician, hit songwriter, successful producer and one time Rolling Stone magazine writer, Jon Tiven.

Lifting the lid off the serious (but fun!) business of making music in the studio and on the road, with some fascinating “I was there” recollections of the ‘who’s who’ of stars he has worked with across more than four decades….

In this digital age where Intellectual Property is constantly under attack or being devalued, it is becoming increasingly difficult for creators to hold onto their creations.

Whether through an unlicensed sample or a straight out pilfer, songwriters have much to fear from the new technology. Anyone with a computer and a larcenous nature can attempt to appropriate someone else’s work – so forewarned is forearmed…

Before I get to this column’s main topic, I would first like to make you aware of my latest musical effort, which hits the stores on record store day, April 21st, a 12” piece of vinyl called “Scrambled Eggs”, by Stephen (I call him Stevie) J. Kalinich. I produced and co-wrote the album.

Stevie and I were introduced to each other by the late great P.F. Sloan, with whom he collaborated as well. Stevie is best-known as the only lyricist who collaborated with all three Wilson Brothers (Dennis, Carl and Brian).

His songs were recorded for their solo efforts, as well as by The Beach Boys, and Stevie has maintained friendships with all of them and their children through the years. Kalinich’s first outings were “Little Bird” and “Be Still” on the “Friends” album, and Brian Wilson produced Stevie’s first solo album “A World of Peace Must Come”.

Most recently Brian and Stevie co-wrote “A Friend Like You,” a duet between Brian and Paul McCartney on his “Getting In Over My Head” album. Which brings us to “Scrambled Eggs”, which used to be called “Yesterday”, but that’s another story.

Over the past five years, several albums by Kalinich/Tiven have been released, but on this one he steps into the limelight as the lead singer. I brought in a few of my friends to duet with him: Black Francis, Ellis Hooks, Dylan Leblanc, Tara Holloway, and the great Bekka Bramlett. OK, gratuitous plug done; now we return to our regularly scheduled programme…..

Victim or perpetrator…

Every successful songwriter at some point, has to deal with theft, either as a victim or as a perpetrator. I was told that if you meet the thieves early enough in your career, you can become inoculated against such infractions later on. It was my good fortune to have the first song I wrote, stolen.

Now making the accusation that your song has been stolen is easy; proving it in a court of law, not so much. Greater men than I have had what I would consider solid cases, only to find that the legal system has strict guidelines.

You have to prove enough music in common between the two songs, but you also must prove access. That trips up many a case, because if you’ve written a song and you can’t prove the party in question had the opportunity to hear it, case closed.

That’s why George Harrison lost part of “My Sweet Lord” and why the New Kids won their George Soule/Percy Sledge dispute. If somebody stole your hit you’ve got a decent shot, but to prove a B-side/album track has been nicked is a more difficult task.

In 1973, my neighbour and running partner Doug Snyder had a four-track studio in his parent’s basement. He and I hunkered down for the better part of a year and made a lot of demos.

By a lot, I mean that when we decided we had enough songs from which to cull a presentation tape, we couldn’t narrow it down to less than 23 songs. We sent out a C60 cassette, completely filled on both sides with our material, to everyone in the music business we had an address on.

It didn’t set the world on fire, but we did get the interest of one Paul Nelson at Mercury, who scheduled us to go into their New York studio for a demo session. We were stoked! Unfortunately, shortly after, he left the label, so we never got to take advantage of this opportunity.

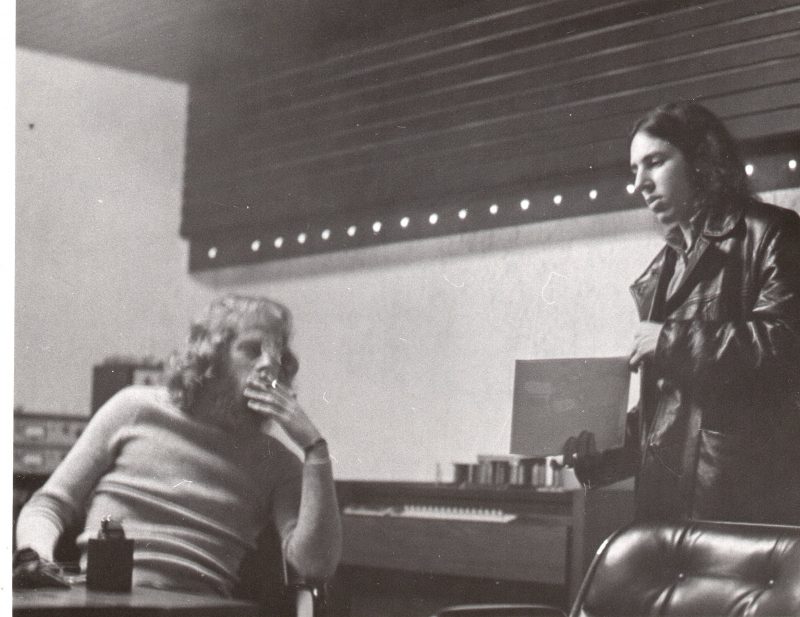

I played it for Andrew Loog Oldham (see picture below of me and Andrew in the studio), ex-Rolling Stones producer living in Connecticut at the time, who sent us into Paul Leka’s studio to cut one of the songs professionally. Andrew thought the song would be perfect for Bryan Ferry, but nothing came of it.

Another song on the tape caught the ear of Kim Fowley, who was trying to get an all-girl group off the ground and thought this song was right for them. I was thrilled, this was a real shot at having a song on a record!

I kept in touch with Kim when I went to work for Chess records in New York in 1975, and when required to travel to Los Angeles that September, Kim made arrangements for me to come see The Runaways in rehearsal. They were strictly a trio – Joan, Sandy, and a bassist named Michael Steele who later came to fame in The Bangles.

I brought a friend of mine along, a struggling out-of-work/out-of-label actor/singer named Rick Springfield. I showed Joan a better way of fingering the chords, and she appreciated the tip. I recall Mike Chapman was there as well, and he was extremely convivial.

About a year later, The Runaways released their debut album. I looked on the back cover and seeing “Gonna Have A Party” wasn’t on it, my heart sank. Oh well, show business!, and promptly forgot about it until a friend of mine asked me along to see the group’s New York debut at CBGB’s.

Stunned but proud…

I was underwhelmed by their set, but when they came out for the encore, they played a song which was unmistakably my “Gonna Have A Party,” renamed “Blackmail.” My music was intact, with a whole new set of lyrics.

I was stunned, proud, but obviously conflicted. I went back after and thanked Joan for cutting my song, but asked her point blank why I wasn’t given credit. “Oh, Kim takes care of all that business stuff”. I assume Joan herself had no personal knowledge of the origins of that song, as I am sure she would have insisted I were given credit, had she known.

I tried calling Fowley to straighten this out, but for some reason he wouldn’t take my calls. As the album sales at the time didn’t seem to merit the worth of me trying to get a lawyer, to regain my proper credit or writing share at the time, I didn’t pursue the matter.

I did have the chance encounter of running into Kim at a New Music Seminar function in the 1990s, and I went straight up to him and said, “I want to thank you for stealing my song. By doing so you convinced me of its worth, motivating me to soldier on.”

I was expecting at least a chuckle, I could have just as easily insulted him. Instead, he sneered “That was just generic.” At which point I just smiled my “go **** yourself smile” and moved on.

After that situation, I made sure when people cut my material I got credit. And I kept the publishing. I learned the hard way about administration rights and how publishers do song and dances about percentages. But it bought me a house.

Not long afterwards, I was falsely accused of stealing songs, and that was also no fun. To have an artist whom I greatly admired engage in character assassination of me is not why I got into music.

In brief, in 1975 Alex Chilton (Box Tops, Big Star) asked me to produce him, an offer I could not refuse. When I got to River City I managed to finish enough tracks to engage the attention of Ork Records, who released an EP. So far so good.

Until I was told by Terry Ork that Chilton’s manager had licensed this record (without my participation, knowledge or permission) to Trio Records of Japan. My tracks were on the first side of the record, and for side two Chilton’s manager provided a cassette of live tracks from CBGBs, calling it “One Day In New York”.

Trio decided to list me as a co-writer for all of the songs of the live side of the record, as they had not been given any songwriting credits for those tracks. Alex was off to Europe and decided to vent to the press about how I had stolen his songs. Nobody called me to ask what I had to say in the matter. Alex was the one doing interviews, I didn’t get to rebut, while he bragged that if he had a gun with two bullets; there’d be one for Dan Penn and one for me.

I figured if I was lumped in with Dan, at least I was in good company. I did not get to make my case until the Alex Chilton biography came out and repeated the charges, at which point I sent the author Holly George Warren my correspondence with Trio Records, confirming my side of the story.

She put the record straight in the next edition (Kindle and paperback), but I still have Chilton fans hating me for stealing his songs. I have enough of my own that I’m trying to unload, thanks, I’ve never needed to appropriate anybody else’s.

Robbed me of my dues…

There were some cases in which people stole my songs and robbed me of my dues, but they were few and far between. The most amusing involved a song my wife Sally and I wrote with Shadow Morton.

Shadow was the creative force behind The Shangri Las, producer of the New York Dolls, Janis Ian and Vanilla Fudge, and with whom we somehow got to be good friends. Shadow would appear, or disappear, in a flash (thus his moniker), and during one of his appearances, he told me how he had met with an old pal at a record label.

This record label pal had asked Shadow for a song for a female pop artist. Shadow’s idea was for my wife and I to write a song with him, about how this young artist was a woman now, and in the middle of the instrumental section she would emit an audible climax.

We wrote and demoed the song and brought in a session singer to sing and make the necessary orgasmic sounds. Shadow presented it to his contact, and his response was “that’s not quite what we’re looking for.”

Except it was. They took our concept and a few of the lyrical ideas for her single, but most notably they had her emulate an orgasm. This was not lost on Mr. Morton. Boy was he pissed. He wanted to sue, I had to talk him down, explaining “you’ll have to prove that an orgasm is intellectual property.”

And then there’s the happy story. Deep background: In 1999, I produced and wrote one of the finest records of my career, Wilson Pickett’s “It’s Harder Now”. It was universally greeted as a triumphant return of a lost master and made quite a splash on radio and in the press.

Every song was mine, most in collaboration with Wilson’s friends like Dan Penn, Donnie Fritts and Don Covay. A good portion of the record I wrote with Wilson, his organist Sky Williams and my wife Sally, and one of these songs was “It Ain’t Easy.”

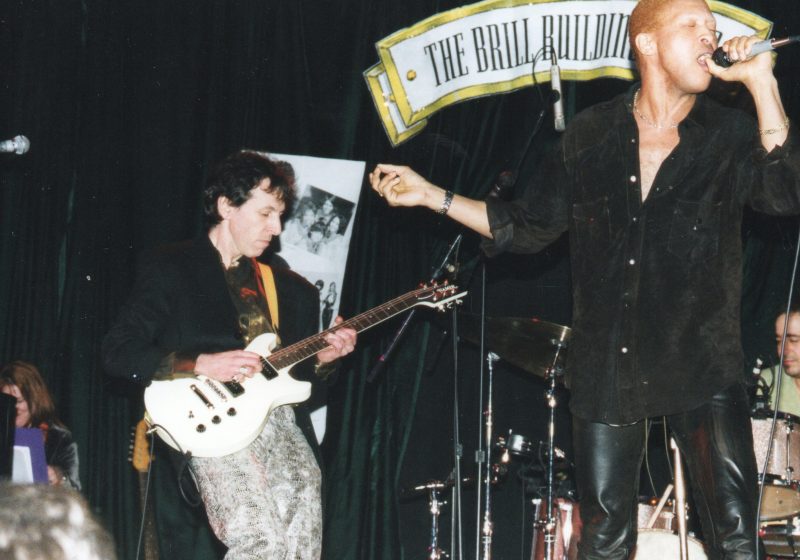

Jump forward a year or two when I began producing a new (and younger) traditional r&b singer named Ellis Hooks. Looking for someone younger to carry the torch for Wilson, Otis and Sam, I discovered Ellis, who had the voice, attitude, and life story from which to draw.

I played the Ellis material for record companies and managers, trying to find somebody in the business to get behind it. One of the managers was keenly interested and wanted in, but Ellis had let me know in no uncertain terms that he wanted me to co-manage him. So I let this guy know that I had to be included on the management side or Ellis wouldn’t be happy, at which point he said thanks, but no thanks.

After a lot of juggling, months later I finally landed a label deal for Ellis with Artemis, and we started to put finishing touches on his release. As the label began playing it for radio programmers and press, we heard about a similar artist on a major label. Radio people were saying they would only play one “Neo-Soul” artist, and there was a lot of money behind the other guy, so we were screwed.

This artist had an EP out to radio already that was creating a buzz. So, I got the publicist for the label to get me a copy of the EP, so I could see for myself why the comparisons were being made.

I looked at the credits: Spotting that the guy who had passed on Ellis’ management was indeed managing this guy. I started by reading the bio. It was literally the same bio I wrote for Ellis, practically word for word, except with this artist’s name substituted for Ellis’.

I put on the EP to listen to the first song, which happened to be called “It Ain’t Easy.” Any guesses as to what it resembles? It’s the same song musically as the one I wrote with Wilson Pickett with the same exact title, AND they were foolish enough not to change the title.

No shit Sherlock!

Time to take it to the bank. I called BMG Music, the organisation that represented my publishing share of the song and informed them of this alleged musical larceny. Their reply was, “Sure. Everybody thinks their songs get stolen.” I told them I’d Fedex them a CD with both songs and they could decide whether it was worth pursuing.

The next day, my phone rang fairly early in the morning. “They stole your song!” No Shit Sherlock, and they were stupid enough to keep our title. “We’ll get 75% of their composition!”, 60% would do fine by me. I called Wilson to let him know.

“How much of my song do I have now?” he asked. “25%. You’d have 18.25 percent of the new song, or somewhere thereabouts.” A long pause. “I’m not interested in 18% of a song I have 25% of now.”

I then tried to convince Wilson that the deal was a good one, but he wasn’t having any of it. I gave him the phone numbers of all the individuals I had spoken to and said if you want to try to improve the situation, be my guest.

I didn’t hear anything from him or my publisher for about a week, so I gave BMG a call to find out what happened with that song. “You got all of it. 100%. Wilson wasn’t accepting a fraction. And you each got $5k for your trouble as a bonus.”

You don’t want to mess with ‘The Wicked’. (Wilson Pickett pictured below, with The Tiven family). He had been around the block a few times. The essence of many of these kinds of cases is access– if you can prove the “borrower” had definitely heard the song they are accused of plagiarising, you have a leg up; the crucial link that gives juries pause for doubt.

By the way; Ellis Hooks and I went to this artist’s New York showcase and introduced ourselves, which was a bit awkward due to the disparity in which the record industry embraced the two artists.

Ellis was the Real Deal, and as such had to beg, scrape and plead for every break he got.

This artist, on the other hand, was seemingly plucked by the corporate powers that be, handed a million-dollar budget for unlimited promotion, and seemed destined for success.

The artist seemed nice enough, and years later got in touch with me to express interest in recording the song “I Believe In Elephants” (which I wrote with Stevie Kalinich), but it never came to pass.

Good singer, but he never found the person/producer who could present him in a way that he was comfortable with, and he didn’t seem to be able to make the most of his opportunities.

I was lucky to have been able to get the case of “It Ain’t Easy” resolved to my satisfaction without even hiring an attorney, never mind going to court. Juries are fickle, and I’m not convinced that ‘The Truth’ always prevails.

I would be hesitant to put a lot of my money into trying to settle a case, even if I knew I was 100% in the right. The song would have to have generated a great amount of income in order to defray the attorneys’ and court costs, and chances are if such was the case, I’d be up against a powerful organisation with greater resources than I.

So…That’s my story and I’m sticking to it. Anybody who says different wasn’t there!

By Jon Tiven

Picture credits:

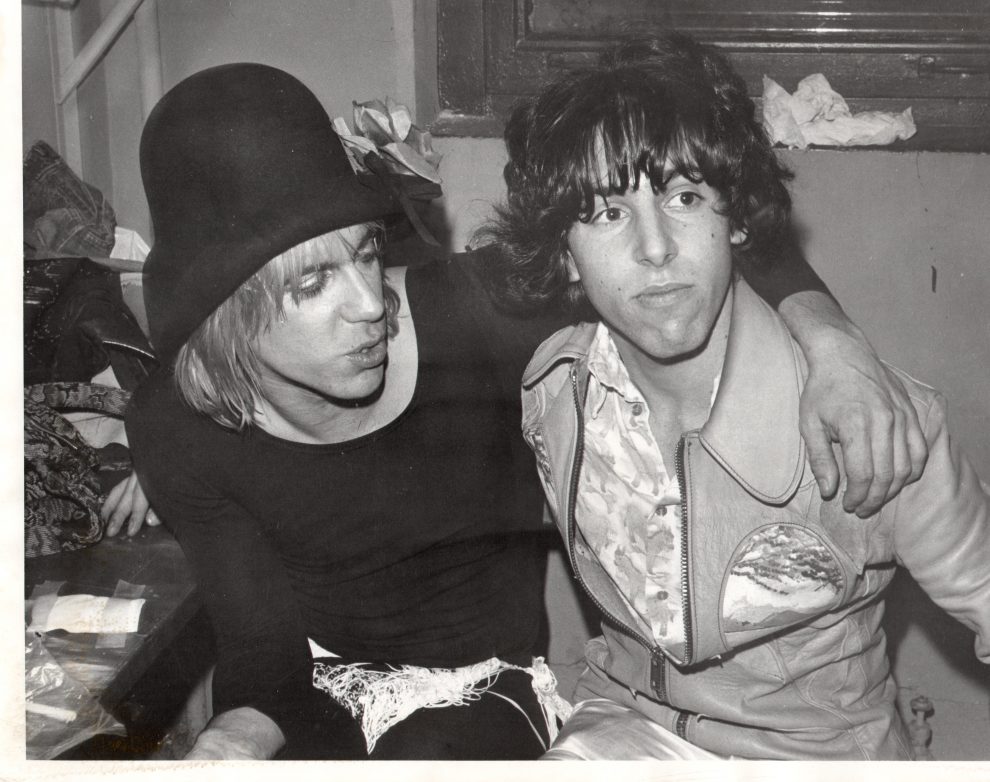

Jon and Iggy Pop (1974) : Seth Tiven.

Jon with Andrew Loog Oldham: Gary Lucas.

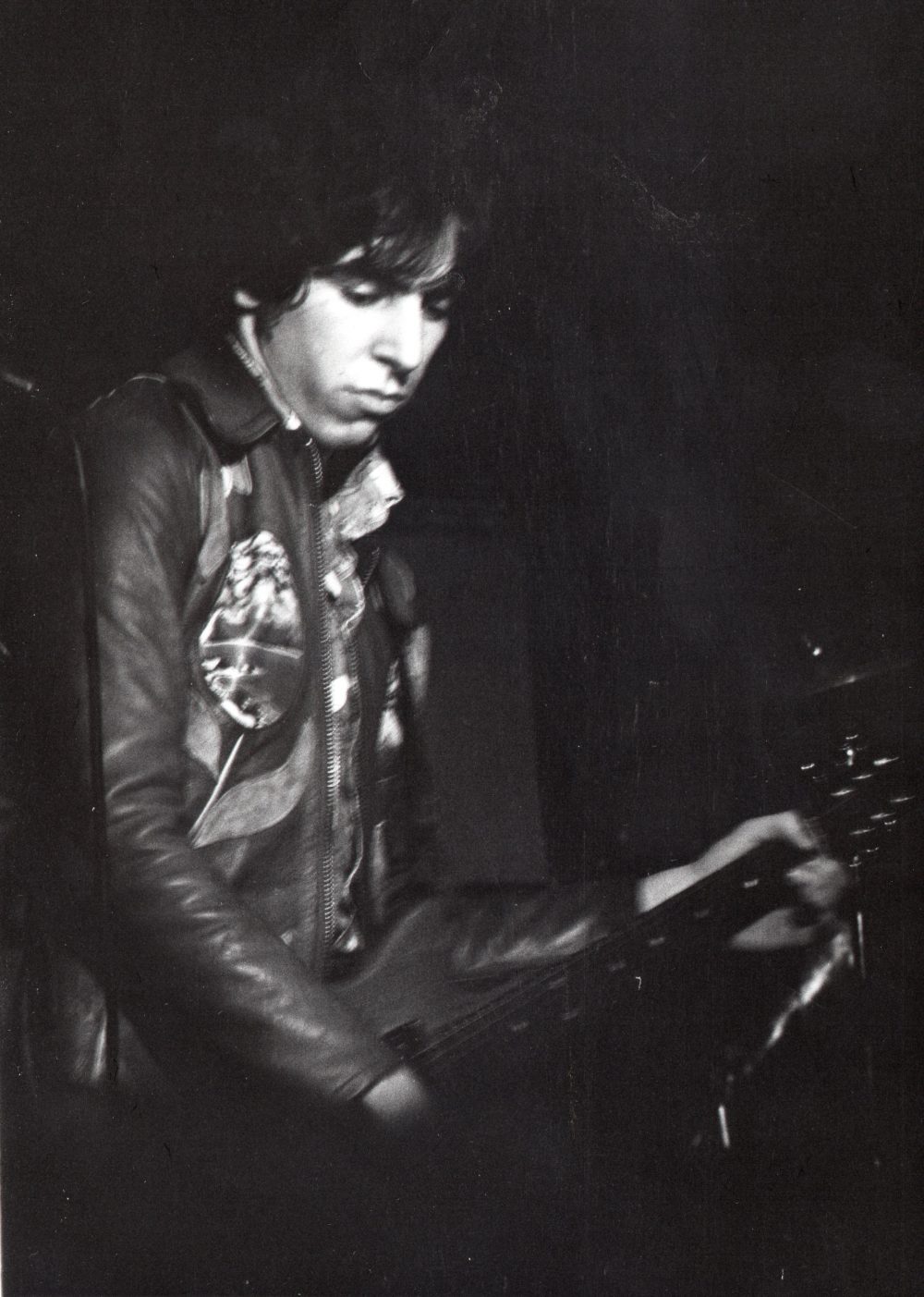

Jon on stage with Big Star, Max’s Kansas City, 1974 (black & white image) : Linda Danna.

Jon with Ellis Hooks: Sally Tiven.

Recent Comments